This is an episode from the “What Makes Us Human?” podcast's fourth season, "What Does Water Mean for Us Humans?" from Cornell University’s College of Arts & Sciences, showcasing the newest thinking from across the disciplines about the relationship between humans and love. Featuring audio essays written and recorded by Cornell faculty, the series releases a new episode each Tuesday through the spring semester.

Recently, a senior U.S. Navy official wrote “we own the oceans.” In the 18th and 19th centuries, when the British Empire was at its height, the British navy would have said the same. But is it really true—do powerful nations own the world’s oceans? And if not, who does own the planet’s water?

This question is essential to what makes us human. Water is life. None of us can survive without water. If an individual, a corporation or a country monopolizes water, selling it for the highest price or controlling it for political gain, then those without money and power will suffer.

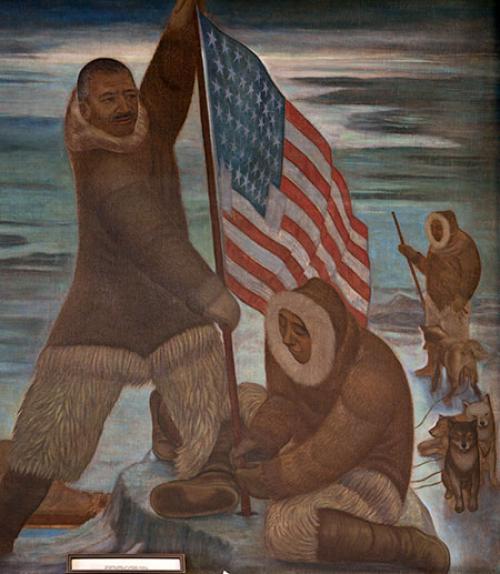

Some believe the oceans are a global commons and owned by everybody. I’m in that camp. But right now that is not the dominant view of those in power. Today, nations are trying to privatize the oceans. The North Pole, the ocean at the top of the world is being claimed right now by the countries in closest proximity to it: Norway, Denmark, Russia, United States and Canada. Russia even planted an underwater flag on the Arctic seabed to strengthen its claim in recent years.

Within the United States itself, the question of who owns the water varies by state and region. In the Eastern United States, east of the Mississippi, the people who own land on the shores of navigable water – that is, waterways that would support a small craft or a log for instance –also own the adjacent water.

West of the Mississippi, water use rights often belong to those who settled the region first. Think about that. Too bad if you arrived recently and didn’t realize it. This water monopoly, called “prior appropriation,” is built into U.S. law and culture. It has prompted people to migrate, to perish, or to haul water with them.

And even when there’s plenty of water, pollution has often made it impossible to use, particularly in the eastern United States. Water degradation from, say, blue-green algae blooms, lead in drinking water, or ocean dead zones are all threats to human survival.

When any resource becomes scarce, the ownership of that resource becomes intensely important. And so right now it is urgent for us to ask this question: is water ownership a privilege—that is, a commodity that some can capture and sell—or is it a common good, a right to be enjoyed by all?

In 2010, the U.N. General Assembly adopted a resolution affirming the human right to clean drinking water and sanitation. Water must be sufficient, safe, accessible and affordable under that resolution. That is, its cost cannot exceed three percent of a household’s income. That motion passed with 122 nations voting in favor. No nation voted against the resolution, but, alas, forty-four nations abstained, including our own, the United States.

On the other hand, international trade agreements tend to treat water not as a human right but as a “tradable good." Free-flowing lakes and rivers are an exception, but once their water is used for industry, hydroelectricity, or municipal water systems, interestingly, they become subject to international trade law. Businesses are then welcome to capture, commodify and privatize that water.

And so we find ourselves at a crucial cross-roads. Will we allow a few private entities to monopolize the world’s water? Will a few nations or corporations allow the majority of the planet’s population to pay or perish? Or will we work together to protect our water as a common good and a human right? There may be no question more important to what makes us human in the 21st century.