Before 2009, when the TV series “A French Village” (“Un village français”) began, a mythology persisted among ordinary people that French citizens protected Jews during the German Occupation, according to scholar Daniel R. Schwarz. “Every family believed its ancestors belonged to the Resistance.”

Not so, Schwarz argues. Rather, France deported 76,000-78,000 Jews, and under the Vichy government, “as the war progressed from 1940 to 1944, many of the same French people were collaborators, then bystanders, and finally Resistance members,” said Schwarz, the Frederic J. Whiton Professor of English Literature and Stephen H. Weiss Presidential Fellow in the College of Arts and Sciences. “After the war many people ‘forgot’ that they had been collaborators or bystanders and ‘remembered’ that they played an active role in the Resistance which they may have found attractive very late in the occupation.”

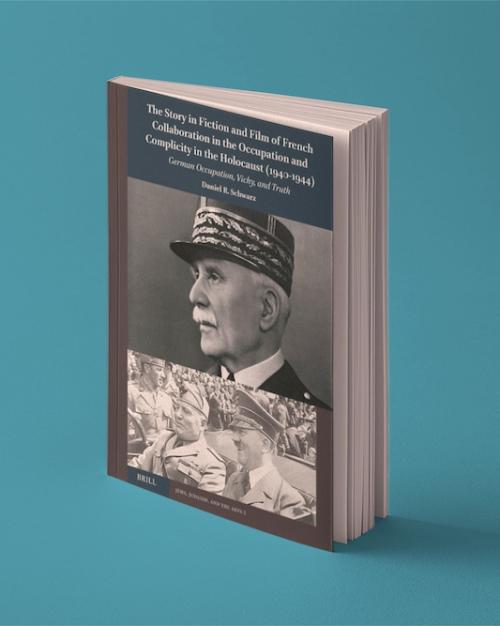

“A French Village,” which ran 72 episodes from 2009 to 2017, played a role in correcting the narrative, he said. It’s one of many works he examines in “The Story in Fiction and Film of French Collaboration in the Occupation and Complicity in the Holocaust (1940-1944): German Occupation, Vichy, and Truth,” which was published in July.

In the book, Schwarz shows how the dominant narrative of the occupation years imaginatively selected and arranged the presentation of neglected and suppressed facts. He guides the reader through films – fictional and documentary – and novels produced since the Occupation that have corrected the history from the “official” and erroneous one to an accurate depiction.

The author of more than 20 books, Schwarz also published a book of poetry in September, “The Garden of My Saying,” which speaks to Holocaust issues.

The College of Arts and Sciences spoke with Schwarz about his new books.

Question: You write of an official history that was adopted and spread about the role France and the French people played during the German Occupation. Who created this narrative and for what audience?

Answer: Charles De Gaulle wanted to re-establish France as a major power and regain what he believed was its proper role since the 17th and 18th Enlightenment, namely as the leader of European culture and civilization as well as of creative and intellectual energy. His audience was primarily France, which had been humiliated by its defeat and subsequent collaboration and complicity.

Q: Which of the works you discuss made particularly bold or controversial statements in their time? Did any of these authors or filmmakers take risks in contradicting the “official” history?

Certainly, Alain Resnais’ early post-war documentary “Night and Fog” (1956) ran into issues with French censors and the protesting German Embassy. Marcel Ophuls’ “The Sorrow and the Pity” (1969) challenged the myth of widespread Resistance and reminded the French of their anti-Semitism. It was banned from French TV until 1981.

Two films of Louis Malle had a great impact on revising the story of French collaboration and capitulation and exposing anti-Semitism in France: “Lacombe, Lucien” (1974) and the autobiographical “Au revoir les enfants” (1987). So did François Truffaut’s “The Last Metro” (1980).

Q: Why are works of art like fiction and movies especially effective in sharing historical narratives?

Films often reach a wider audience than fiction; for many people the visual is more effective. The series “A French Village” has been particularly effective in showing recent generations what really happened in France. The 2014 French Nobel prize winner Patrick Modiano has been obsessed in his fiction with shining a light on French behavior during the occupation.

Q: How have your recent trips to France influenced your perspective?

Since 1961, in my many visits to France, I have watched France become more alert to its past as it discovered how some of its leaders collaborated. I also see and read about how even in the 21st century, France has continuing instances of anti-Semitism.

Over the years, what happened in Vichy under the Marshal Pétain regime has come to light, and we have learned how sometimes the French were more vigorous than the Germans in pursuing Jews, taking their property and sending them to concentration and death camps. Recent French Presidents have offered increasingly detailed apologies for the pro-Nazi behavior and the collaboration of Pétain, the leader of the Vichy government, and his colleagues.

Q: Would you tell us about the connection between your research into Holocaust history, especially in France, and your poetry that speaks to Holocaust issues?

A: A section of my recent poetry collection is entitled “Exploring Jewish Heritage’’ and reflects my identity as a Jew, as well as my confrontation with what might have been had I, born in 1941, lived in Europe. I quote from “The Shape of Memory in Prague”:

Once again, I learn

What Shoah means.

In synagogue, now a museum,

I examine children’s

art from Terezin—

dark grey, heavy lines;

mysterious large intrusive shapes—and

photographs of their creators.

I feel bound to those

sad, dark-eyed victims,

knowing I belong

to an ancient people

that stared down

obliteration,

outlived death camps.